It would have seemed implausible in an Indiana Jones movie… A Turkish DIY fanatic swings a hammer in his basement, and breaks through the wall to reveal a hidden underground city, going deep into the earth below, and dating back two thousand years.

While subterranean cities are not unknown in Turkey – they were often relied on to hide from attackers – Derinkuyu, in Cappadocia, is on a staggering scale.

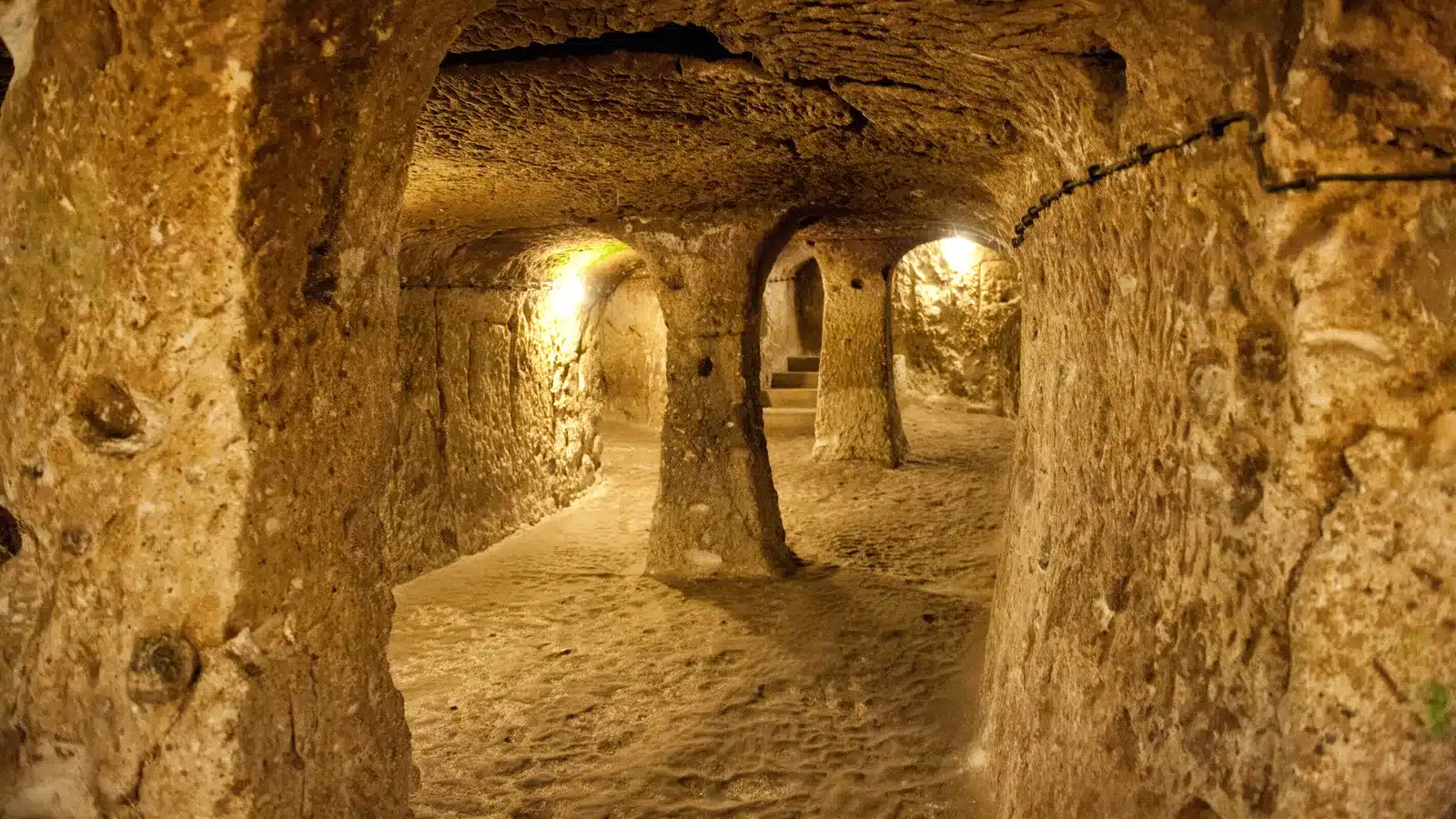

It stretches downwards by 85 metres into which are compressed 18 levels of homes, storage, cellars, stables, chapels and even a spacious schoolroom with a barrel-vaulted ceiling. It would have housed around 20,000 people for months at a time, and may have linked to other smaller, nearby underground refuges through a network of tunnels.

While Derinkuyu’s discovery is archaeological old news now (that first basement breakthrough was in the 1960s), excavating it fully took decades, and it remains a site of study and still some mystery.

Who made it and how?

The earliest habitations were likely dug by the Hittites around 1200 BC, but later added to by the Phrygians hundreds of years later. Perhaps even the Christians turned a hand to enlarging it in the first centuries AD. No one knows for sure. Even the tale of its discovery is contested. Some claim it was a farmer in search of chickens he witnessed disappearing into a crack in the wall.

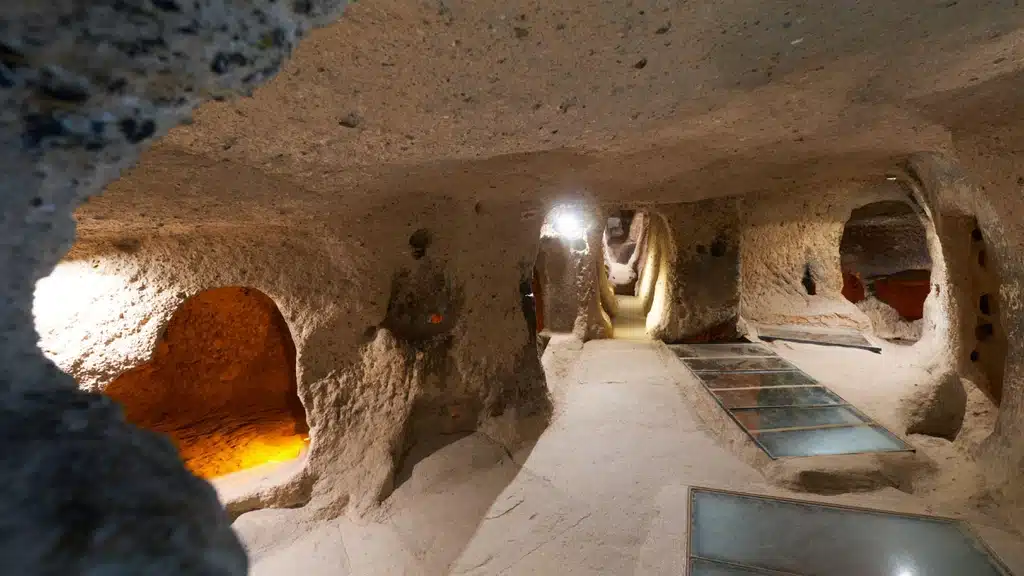

What is more certain is how the creators managed such a feat. The region’s stone, formed from volcanic ash, is soft, so not difficult to mine by hand. It would have been easy enough for individual families to carve themselves a house (often with bedrooms, kitchen and a bathroom), and for the city to grow organically as thousands of amateur miners set to work.

Elaborate airways and burglar deterrents

But that doesn’t detract from the achievement. There are thousands of ventilation shafts dug out to ensure attackers could not stifle the air supply. Huge, rounded stones were used to roll across and seal incoming tunnels. The deliberately winding and narrow passageways were designed to confuse invaders. And then there are the waterways carved to deliver fresh water to each level.

It’s thought that small sections of the city were still being used in 1923 until a population trade agreement between Turkey and Greece saw the last inhabitants with any knowledge of its history rehoused far away, and Derinkuyu’s narrative faded away.

In the decades following its rediscovery it has become a tourist attraction – or at least part of it – and this remarkable example of ‘civilian mining’ has been granted UNESCO World Heritage Status.

One more thing…

Derinkuyu is a remarkable piece of history, and one of its greatest feats is the depth of the wells dug for water. But how deep do you need to go to find the oldest water in the world?

That particular breed of H20 lies nearly two miles down, at the bottom of the Kidd Creek Mine in northern Canada, and is thought to have been trapped in the rocks there for well over two billion years. (The initial discovery a few years ago won Dr. Barbara Sherwood Lollar of the University of Toronto, the Gerhard Herzberg Canada Gold Medal for Science and Engineering.) The mine has usually harvested copper, zinc and silver, but an exploratory drill hole looking for more ore stumbled on the water, and a surprising amount of it. “People assume it must be tiny amounts,” said Professor Sherwood Lollar, “but it’s bubbling right up at you.” The team aged it by analysing dissolved gases, including helium, argon and neon. Though colourless when originally recovered, it turned orange in contact with oxygen as the dominant minerals became active. And, in fearless pursuit of science, Sherwood Lollar actually tasted it, describing it as highly saline and musty smelling, and more viscous than tap water, similar in consistency to thin maple syrup. So don’t expect to see it bottled and at the back of the bar any time soon