Trips to the “vault” were once routine for geoscientists combing Hudbay Minerals’ land package in the Flin Flon camp of northern Manitoba for new deposits. The dedicated room stores more than 80 years of exploration information in floor-to-ceiling filing and map cabinets, including floppy disks, project reports and drill logs: an explorer’s treasure chest, but an inconsistent one prone to gaps, duplication and incompatibility.

Now, thanks to a new data management system, the vault is becoming obsolete but the priceless files stored within are finding new and greater value on a central server.

Since 2011, Senior GIS Specialist Kenda Kozar from Hudbay’s original headquarters in Flin Flon has been working with Geosoft to upload geophysical data onto DAP, a secure geospatial server everyone can access to catalogue and manage exploration results. Concurrently, the company is implementing Microsoft’s Sharepoint to provide document control for internal links to other exploration information (reports, drill logs, etc.) related to a particular drill hole or project area.

The exploration team believes the new system will be instrumental in reaching its main goal: to find at least one new mine in the Flin Flon camp using data already collected.

The Flin Flon camp generates data faster than weeds propagate on a prairie farm. The greenstone belt that straddles the border between northern Manitoba and Saskatchewan is one of the most prospective VMS regions in the world. More than 30 deposits rich in copper, zinc, gold and silver have been discovered there and hundreds of millions has been spent on exploration over the past century. Many mines and projects, both past and current, dot the landscape.

Hudbay has been operating in the area since 1927, when the miner incorporated to develop the Flin Flon base metal deposit, considered one the largest industrial developments in the West at that time. While the company has since expanded into Peru, it remains active along the belt, with current claims covering an area of about 340,000 sq km. Hudbay’s 2007 discovery of the Lalor gold-copper-zinc mine – the belt’s second largest deposit – breathed new exploration promise into the region.

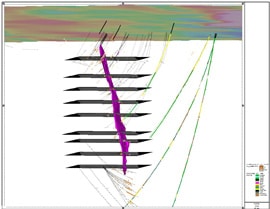

Over the decades, Hudbay has drilled about 17,000 holes, mostly within 300 m of surface. Geophysical data exceeds 260 gigabytes and more than 25,000 surface rock and soil samples have been collected, assayed and catalogued.

Managing the growing amounts of paper and digital data had become a monumental challenge. Geophysical information, mostly surface and borehole EM results, seismic data and some gravity and resistivity work, was saved in an unaudited folder system. Project files contained multiple versions of the same surveys as well as non-exploration files. Interpretations of results were often lost in personal e-mail folders, and paper maps in the vault were incompatible with digitized information.

But with the help of Geosoft’s data specialists, Hudbay is making progress scanning, reviewing, organizing and cleansing geophysical data, which represents the largest exploration database for the area. According to Kozar, a driving force behind the project, the company has uploaded about 80% of the information on its active projects – or 11,500 datasets – to the DAP server. In addition, about 90% of company’s raster data, the more than 20,000 maps created before 1988, has been scanned and is being georeferenced.

“While the process was similar to other engagements we have had with exploration companies at a high level, the detailed steps in the preparation stage were rather unique to Hudbay,” says Henry Wang, Geosoft’s technical lead on the project. “We had to use skilled resources and data specialists to manually review and cleanse most of the ground geophysical survey data.” To help with the task, Geosoft assembled a team in its Brazil office to review and georeference the information and enter metadata into the prepared datasets.

Back at Hudbay’s Flin Flon office, implementing the exploration information management system (EIMS) has not been without its growing pains partly because of a natural resistance to change and partly because of the state of the exploration files.

Much of the data was stored in different formats and scales with inconsistent headings. Finding metadata proved challenging in some cases. GPS readings taken on or close to UTM boundaries had to be scrutinized for accuracy, and converting files from local grid systems was difficult.

But Hudbay’s data managers are gradually overcoming the challenges. “We have improved our workflow now that everything is in the same spot,” says Data Management Geologist Maggie Currie. “We can integrate geophysics, geology and geochemistry together to create better 3D models. And people don’t have to spend as much time manipulating the data, they can just access it and start their research.”

With much of the heavy slogging completed, Hudbay’s explorers are increasingly buying into the DAP concept, uploading and retrieving information to and from the server as routinely as they once made visits to the vault. The numbers speak for themselves: while just over 500 datasets were accessed on the server in the whole of 2012, more than 3,000 registered a hit in the first four months of 2014.

Despite the extra time required to prepare the data for upload, having a central location where all the information about the Flin Flon camp is reliable and accessible will ultimately prove rewarding. “If we took the cumulative time that everyone will save in the exploration group, not just this year but over the next five to ten years, the minimal increase in time it takes to push the information up to the server will pay for itself many times over,” says Chief Geophysicist Peter Dueck.

He says the EIMS takes some of the worry out of staff turnover, which can be high in the cyclical exploration industry. Instead of geoscientists leaving the company with a new mine stored only in their heads and/or e-mail folder, valuable information resides securely on the server with accessibility to all. And Hudbay’s geologists and geophysicists are already working more closely together because of the ease of collaboration the system provides.