Turning a tap and watching fresh water pour out isn’t as common as you might think.

According to UN-Water, around 2 billion people lack access to safe drinking water and the urban population facing water scarcity is predicted to double to between 1.7 billion and -2.4 billion by 2050.

Groundwater Relief connects hydrogeology experts with humanitarian and development organisations to supply safe and sustainable water sources to underserved communities worldwide.

“I started off work in the humanitarian sector as a WASH [water, sanitation, hygiene] engineer and it was fairly clear, fairly quickly that there was a real lack of expertise in understanding what was going on underground,” says Geraint Burrows, CEO of Groundwater Relief.

The non-profit was launched to fill the knowledge gap around groundwater and to help uncover and manage this hidden resource for those in need.

“Water supplies are, in general, now under pressure or being over utilised. Surface water is an easy water source for people to see, develop, and manage,” explains Geraint.“Groundwater is invisible. It’s therefore much more difficult to regulate and manage.”

Groundwater accounts for about 30% of the world’s freshwater supply and is a crucial resource for drinking water, agriculture, and industry.

Groundwater Relief in the field. (Credit: Groundwater Relief)

Water as a shared human need

Groundwater Relief has a global membership of over 450 experts from 56 different countries. While the focus is on hydrogeology, Geraint’s team is driven by a mission beyond the science.

“Ultimately, we’re trying to serve families and individuals who lack access to a safe water supply to support them,” he says.

They assist organisations who are trying to supply water to vulnerable people, in-country institutions responsible for managing water supplies, and local companies.

“We approach them with the idea of capacity building by engaging our worldwide experts to work with local teams to improve knowledge and understanding and improve the way the projects and money is spent,” says Geraint.

“We can advise both in terms of the broader development, but also in setting up monitoring programs and trying to manage water resources.”

The success lies in validating their groundwater models against real-world conditions. The ultimate reward is knowing that more people will have access to fresh water.

“There’s nothing more satisfying than drilling a borehole and seeing water being pumped out for supply,” he says.

Capacity building or training skills on site is a key part of how Groundwater Relief makes an impact. (Credit: Groundwater Relief)

Groundwater’s vital role in refugee camps

Currently, there are around 37.6 million refugees in the world – the highest ever recorded by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Refugee camps are continuing to grow as environmental, political, and economic issues force large groups of people to relocate.

“Every situation is quite different. Ultimately, you are working with people who’ve often lost almost everything. They’re not in refugee camps as a matter of choice, but as a matter of necessity,” says Geraint.

However, their struggles don’t end with escape. Once they reach the safety of a camp, access to water becomes a vital concern – and one that only grows the longer a camp lasts.

If water sources become strained, tensions can escalate between nearby communities and the camps.

“The minimum average lifespan of a refugee camp is 20 years, at least. These are long-term dwellings,” Geraint explains, “If your resources start to be depleted or your boreholes stop pumping water: that can cause problems,”.

Drilling boreholes and discovering new water supplies can help to alleviate tensions as well as increasing water access.

Drilling for water at sunset. (Credit: Groundwater Relief)

Increasing water supply in Sudan

Over 120,000 refugees rely on water under the Bentiu Camp in South Sudan. To improve water access, the team developed a groundwater model to identify new drilling sites.

”We were very fortunate to have Thomas Krom [segment director, environment at Seequent] as one of our members. He was very kind to develop the first Leapfrog models for us when we were working in South Sudan, Geraint says

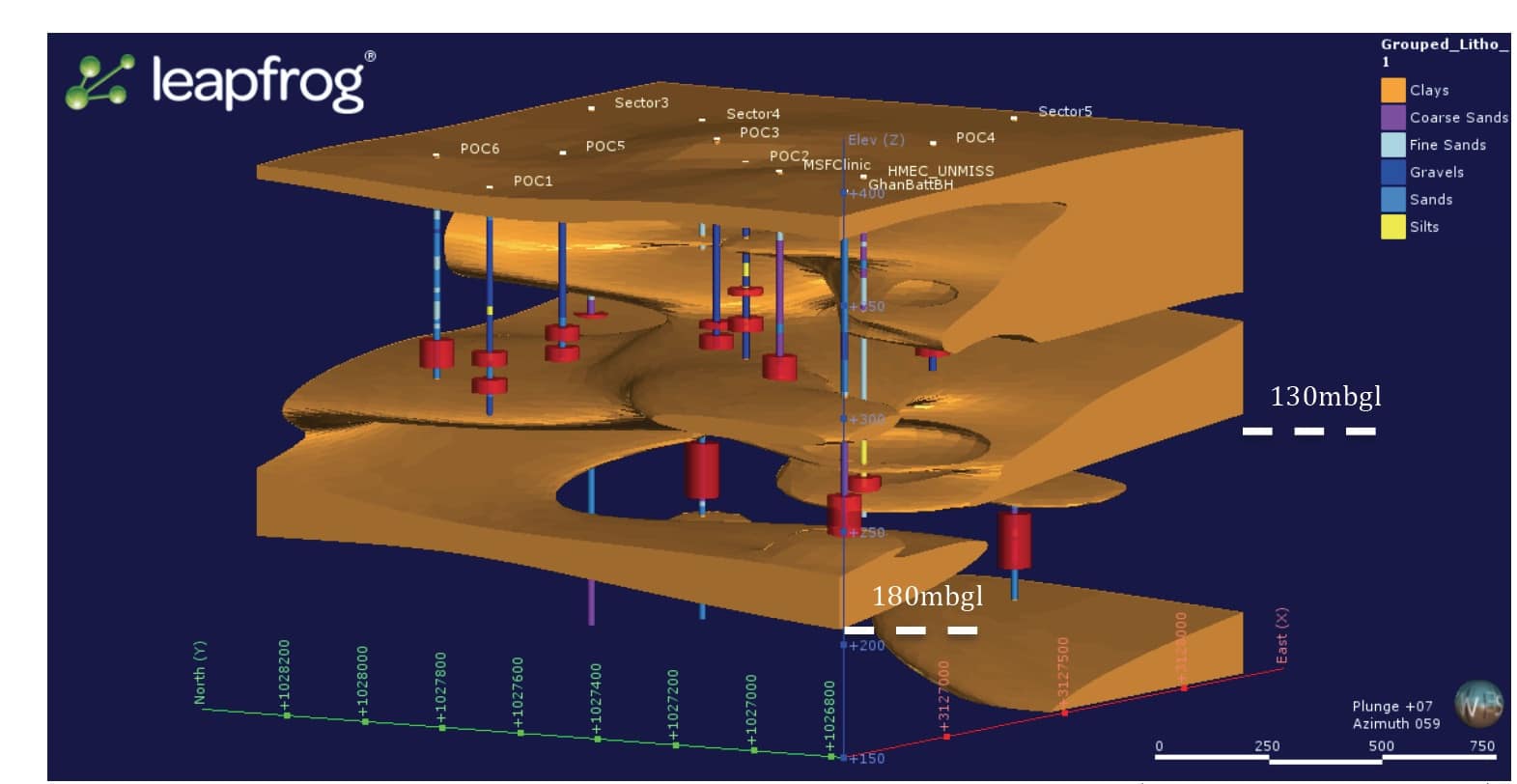

The team used records from 10 to 12 boreholes to create a geological profile with Seequent’s Leapfrog software. These models help to provide an understanding of aquifer systems before drilling and effectively communicate findings to decision-makers.

After building the 3D groundwater model, they were relieved to discover additional water resources beneath the camp.

“We saw that there were two systems: a deeper system and a shallow system. And then that was validated through pumping test data and water quality testing data. It helped to determine specifications going forward for water supply for the camp.”

Leapfrog model of the Bentiu aquifers. (Credit: Groundwater Relief)

Water for the world’s largest refugee camp

Since early 2019, Geraint’s team has been working in partnership with the University of Dhaka in Bangladesh to develop the first groundwater model of the aquifers beneath Cox’s Bazar – host to the largest refugee settlement on Earth.

Nearly 1 million refugees live in camps in the area. Besides drinking, water for washing is crucial to prevent the spread of disease in these densely populated communities. Water demands are high.

“This model was able to, in effect, tell the international community about the water supply underneath the Rohingya refugee camp. There was a large basin of water there, which is currently being able to maintain the supplies of water for those refugees,” says Geraint.

“We’ve been able to predict the impacts the withdrawal will have on the host community and being able to suggest mitigation measures.”

Groundwater Relief has over 400 members who lend their skills to help find water for vulnerable people worldwide. (Credit: Groundwater Relief)