When a solar storm is in the forecast, Jannetta (Jae) Robinson crosses her fingers and turns on her smartphone. She’s using CrowdMag, an app that’s crowdsourcing magnetic data to help us understand one of the Earth’s invisible forces.

“The magnetic field protects us from things like solar flares and radiation, but it also has an effect on us and our electrical devices. In this age, that’s super important,” explains Jae.

She’s researching changes in the Earth’s magnetic field caused by solar weather as an intern with the Research Experience for Community College Students program run by the Cooperative Institute for Research in the Environmental Sciences (CIRES) at the University of Colorado.

Her project uses CrowdMag on four smartphones at her base at the University of Colorado Boulder as well as one at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, closer to the Earth’s northern magnetic pole where the magnetic signal is stronger.

“Each intern is doing a different project. There are some people studying rivers, riverbank sediments, and birds. And somehow my project relates to all of theirs. So, that’s really cool,” says Jae.

There are many important questions about the Earth’s magnetic field surrounding satellite navigation, space weather, and ecology. Recent studies even that show that it can have physiological and psychological effects on some people.

So, how could we collect the massive amount of magnetic data needed to get the answers?

Geomagnetics, let’s make an app for that

CrowdMag interns at CIRES get a chance to run a research project and "explore our magnetic world." (Photo credit: Rick Saltus, CIRES)

CrowdMag was born between bites during a lunchtime conversation at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

“We thought, well, all phones have magnetometers in them and there’s billions of phones. And even if a small fraction of the people on the planet were collecting data, that would be a lot of data,” says Rick Saltus, senior research scientist at CIRES at the University of Colorado Boulder.

“Then maybe there would be enough redundancy that just by aggregating the data we could get something out of it.”

Rick (along with colleague Manoj Nair) also leads the CrowdMag program at NOAA. He mentors interns like Jae who have completed a few years in college and are interested in gaining research experience.

He wants to get geoscience into the hands of more young people. What better way than an app?

“I think the fundamental thing is just that people should realise science isn’t something that happens far away. The important thing is that it makes it approachable,” adds Rick.

NOAA also creates an official model and forecast of the Earth’s magnetic field, used for navigation, every five years.

“The group that I work in at NOAA and CIRES makes the official World Magnetic Model that is used for navigation and every five years we update it. And then we try to project it ahead and say what we think it’s going to do, but that prediction breaks down really fast.”

CrowdMag research projects and data could add the insights Rick’s team needs to make better predictions.

A forecast for space weather

Jae is studying time variation of the magnetic field and how space weather affects it. Her project compares CrowdMag data collected over time to see how solar events impact magnetic readings.

“Hopefully it can contribute to furthering research on space weather and give scientists more knowledge on the solar cycle,” Jae says.

“We could always get lucky if we get a big solar storm when we happen to be collecting data. And maybe then we’ll be able to see something.”

There’s one major challenge with using CrowdMag data: It’s noisy, very noisy.

“A big challenge, as you might expect, is because the sensors in phones aren’t really made for this,” Rick explains.

Finding a signal is much harder with a cell phone magnetometer. It picks up a lot more interference than more specialised devices. A key part of the CrowdMag program is discovering how to make cellphone magnetic data usable.

“It’s a lot harder to find a signal where we are on Earth compared to places like Alaska as it’s closer to the pole. So we’re mostly working with the Alaska data because it’s a little bit easier to find that signal,” says Jae.

“We’ve been able to get a signal there and it shows a little bit of correlation to the observatory data. So that’s pretty interesting.”

One workaround is using data from high latitude areas, where the signal is strongest. Understanding what it looks like there will help make searching for signal in other areas a bit clearer.

Rick sees an even bigger application for studying noisy data.

“What we’re learning about the noise characteristics of the phone can feed into cleaning up the NOAA global database,” says Rick.

“The observatory network doesn’t cover the Earth. There are many parts of the Earth where we don’t have data. It would be great if we could use the CrowdMag data to fill that in, even at lower resolution.”

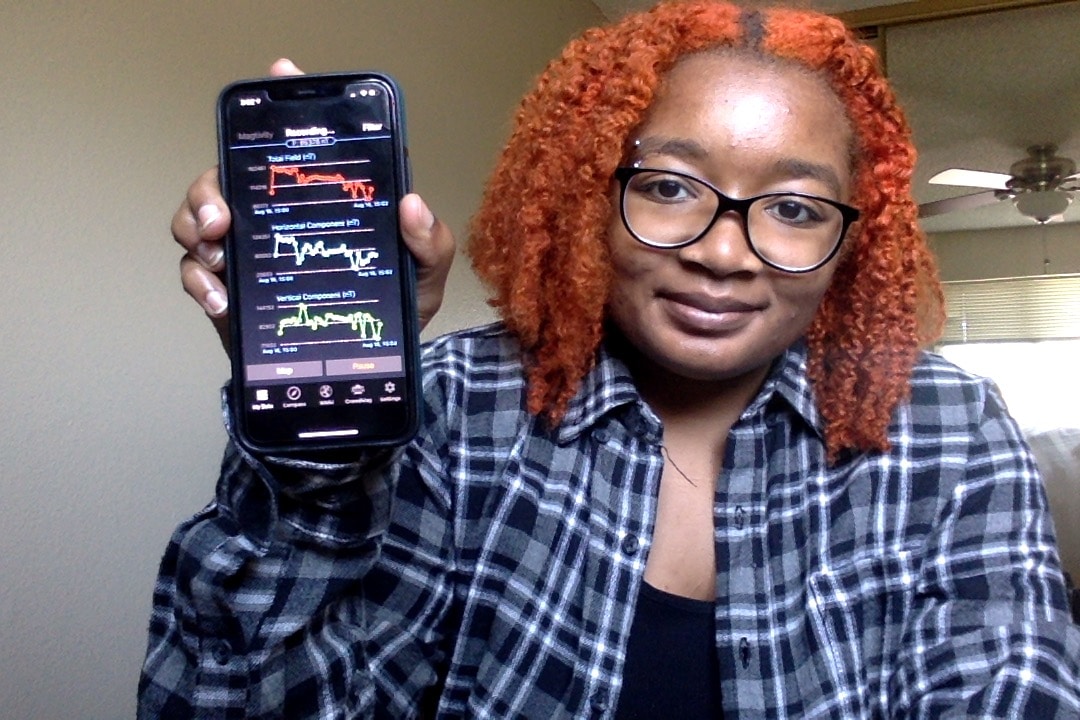

Jae Robinson shows her magnetics data on the CrowdMag app. (Photo credit: Jae Robinson)

Using magnetics to attract future geoscientists

For student interns, like Jae, CrowdMag offers a glimpse into the geosciences. They get hands on with the unseen forces around us, using their own phones as survey devices.

“The phone interacts with the environment in different ways, like temperature dependence, and there’s a bunch of different contributors to the phone noise,” says Jae.

“It’s super interesting to see how an Apple phone versus an Android phone behave differently, and also the differences between the Colorado and Alaska data.”

She also discovered firsthand what a field research project is like. And, similar to her data, it wasn’t as clean or straightforward as she’d expected.

“I didn’t think that we would have so much trouble finding a signal and it was a little frustrating. But, it was step-by-step and then back again. And I think that process of trying to answer the question is my biggest takeaway,” Jae says.

Students also get a chance to work with data and transform it into insights.

“We put the data into Excel and for visualisation we plot it on a scatter plot. We use trendlines to take the noise out. We also worked a little bit in Python, too,” explains Jae.

Students use Excel and Python coding as steppingstones into more robust software, like Oasis montaj that Rick often uses to clean and model data at NOAA.

As a gateway to geoscience, CrowdMag seems to be working.

“I’m a biology major so I’m trying to cross over into environmental science and, after this project, definitely geosciences,” says Jae.

How does the geodynamo work?

The CrowdMag app is also a big citizen science experiment. Anyone, anywhere can download the app and provide data about the field in their location.

The geodynamo is the mechanism within the Earth that generates its magnetic field.

The magnetic field is always doing unpredictable things. Rick sees crowdsourcing as a major way to fill in the data gaps and understand it.

“Even NASA who has these huge mathematical models of the geodynamo still can’t really predict what it’s going to do next,” says Rick.

“One of the fundamental, Nobel Prize worthy type of questions is: exactly how does the geodynamo work?”

With projects like CrowdMag gathering data, maybe the answer will be crowdsourced.